Author, Katy Kan

Globally, as many individuals and corporations trudge on to cope with the economic fallouts brought forth by the Covid-19 pandemic, it is often heartening when we hear of philanthropic activities that aim to bring relief to various social groups. From the provision of daily meals to the marginalised, the creation of employment opportunities for the disenfranchised, the donation of educational resources for the future generation, to acts of solidarity to express gratitude to migrant workers and frontline workers and even love offerings to keep alive the enduring works of the performing arts sector.

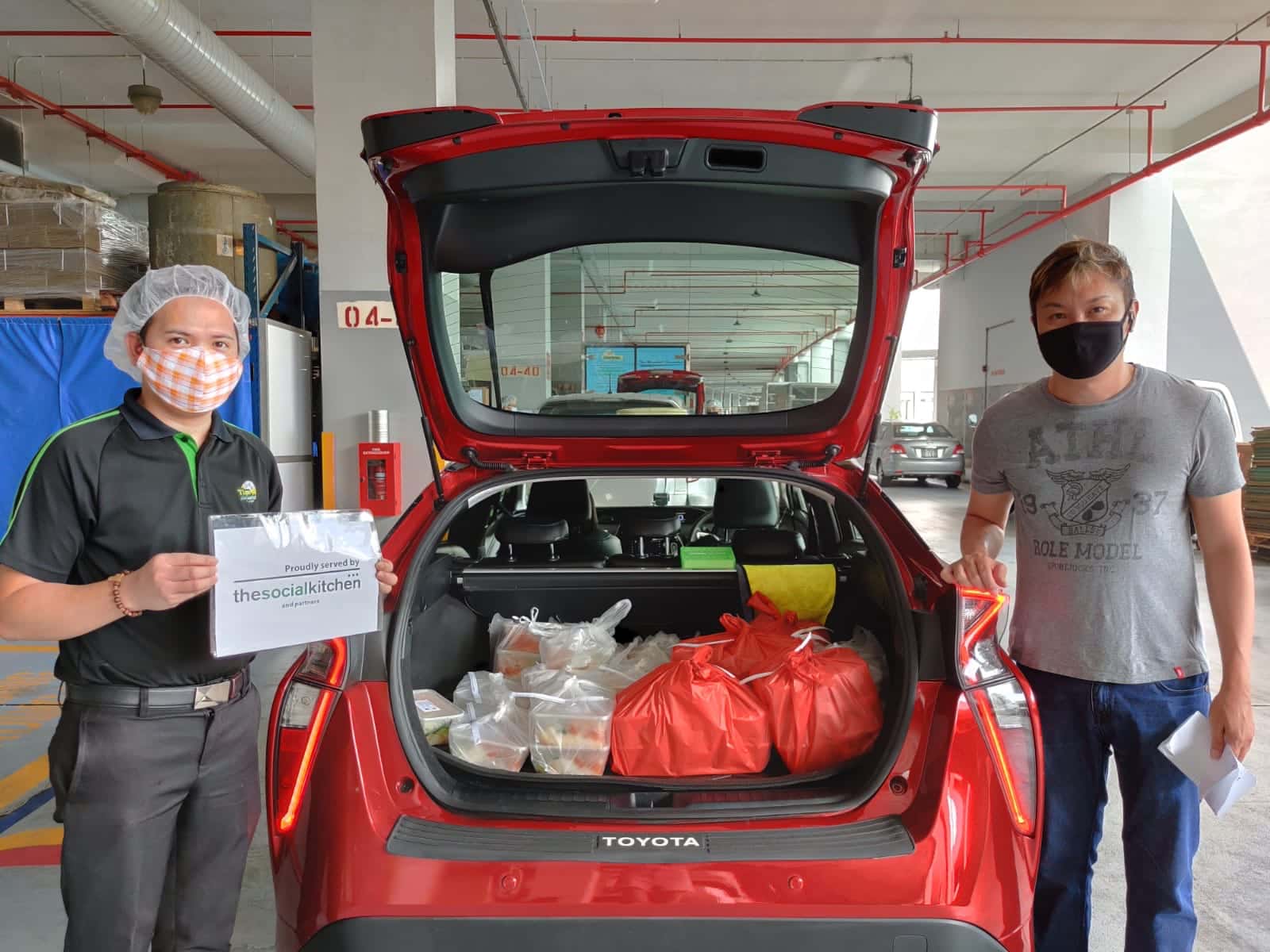

While the heart of philanthropic actions rests on the simple desire to be in solidarity with others; paradoxically, the behind-the-scenes processes and works of charitable works are often much more complex and constantly in-flux. Let’s take the story Project Makan in Singapore for example. Project Makan is an initiative Alvin and Kian Peng of The Social Kitchen (TSK), a social enterprise that manages charities’ kitchens as a central kitchen for food deliveries.

Incidentally, makan is vernacular in Singapore and it stands for eat or eaten in English. Inspired by a FB post that offered a meal to anyone who needed help due to loss of income because of COVID 19, TSK started a heartfelt initiative to feed school-going children (who would have otherwise received lower-cost meals through the public school system under normal circumstance) daily meals during Singapore’s movement control period, or Circuit Breaker. Project Makan soon challenged the founders of TSK to manage multiple stakeholders, a robust pipeline and many unforeseen curveballs since the start of the project.

In partnership with two NGOs, YMCA and SHINE Youth and Children Services, Project Makan started on 10 April with the aim to prepare and deliver one meal a day, every working day to needy children and their families. However, with the extension of the Circuit Breaker till 1 June 2020, what started with 142 delivered-to-doorstep meals for 34 families has ballooned to an overall target of 100,000 free meals or 5800 daily meals. That’s a 40-fold increase in the number of meals to be fulfilled, and a shortfall of $300,000 if sponsors had decided to pull out after the original Circuit Breaker deadline of 4 May 2020.

This was a chicken and egg conundrum that the Alvin and Kian Peng of TSK had to face: commit without the assurance of the needed funds or to pull out by the original deadline of 4 May 2020? The founders of TSK decided on the former. Since then, more food sponsors came onboard and with a creative cost cutting measure in transportation, a shortfall of S$50,000 currently remains.

As for the daily operation of Project Makan, this is where the collaborative effort of YMCA and SHINE Youth and Children Services takes centre stage. In today’s new order of social distancing, this means that the massive task of matching 5800 meals (various dietary requests) from kitchen to deliver to homes, the control of delivery timings, the timely updates of recipient addresses and many general queries are handled remotely by teams from the two NGOs. There is no rest day for the NGOs. They juggle the minute by minute coordination of Project Makan alongside their current daily workload and managing family obligations .

Apart from children and families who are direct beneficiaries of Project Makan, Alvin and Kian Peng ensured that the philanthropic ecosystem that has been created in the process not only meant the creation of employment to restaurants, kitchen staff and delivery drivers from delivery platforms such as GRAB, Singapore Mass Rapid Transit (SMRT) and various logistic companies, it has also become a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) platform for companies that wish to support the initiative of TSK. For instance, Pan Pacific Singapore has tapped on Project Makan to sponsor 20,000 meals.

Yes, in the purest heart of philanthropy, we should always find the notion of solidarity with others. In this sense, Alvin and Kian Peng of The Social Kitchen have shown us boldness in holding true to this ideal in forging forward when financial certainty cannot be guaranteed. But is standing in solidarity enough in today’s highly uncertain world?

Indeed, in a (post)Covid-19 era where economic displacement is certain, donor fatigue will increasingly present itself as a reality that philanthropists cannot ignore. How then can we continue to stand in solidarity with others and not run out of steam? I believe that the philanthropic model that Project Makan by The Social Kitchen has put forward offers an excellent approach to be philanthropic in the 21st century: It’s about not doing charity alone. When we think about it, this isn’t actually new. It’s going back to basics.

It’s about individuals like Alvin and Kian Peng pulling in their resources as a community to raise a village of people. Indeed, it’s about branching out far and wide while being rooted in our core ideals. That’s what Project Makan has done.

Written by Katy Kan

Shadow Puppetry: The Dying Art

Start With One

Do you have an article, infographic, podcast, presentation slides, press release or a key individual from your organisation that you'd like to highlight on Marketing In Asia? Head on over to Upload Your Content for more info.